| Africa’s Iron Origins: Archeological Evidence | 您所在的位置:网站首页 › iron working in africa托福 › Africa’s Iron Origins: Archeological Evidence |

Africa’s Iron Origins: Archeological Evidence

|

Iron’s Material Transformation | Africa’s Iron Origins | Sustenance from the Anvil | Iron’s Empowering Roles | Blades of Power and Prestige | Blades of Value | Sounding Forms | Cosmic Iron | Videos | Home

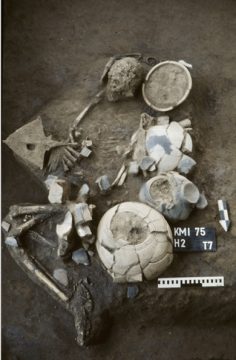

Most contemporary scholars believe that Africans began smelting iron from local ores about 2,500 years ago, but details remain debated. Were these technologies invented and developed in one or several sub-Saharan locales? Were they disseminated with early migrations and trade? However they came to be known to African artisans, iron technologies were quickly adopted and adapted, and large-scale production of iron occurred in several ancient locations. Iron production, use, and exchange defined social and political hierarchies, as confirmed by findings at the archaeological sites of Campo in Cameroon (dating to the 2nd–4th century CE), Kamilamba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (8th–10th century CE), and Great Zimbabwe (13th–14th century CE). Kamilamba | Tomb 7Buried evidence. In what is now the heartland of Luba peoples, in southeast Democratic Republic of the Congo, a burial from the 8th to 10th century CE contained a pierced and richly engraved iron axe blade along with pins that likely once decorated its wood shaft. Next to the skull of the buried man was a forged iron anvil. Grave goods at Kamilamba also included pottery, iron tools, and iron and copper jewelry, the latter probably traded from the Katanga Copperbelt to the south. Only a few individuals were buried with rare items such as the ceremonial axe and anvil. The burial may be an early example of a cultural concept in central Africa that equates kings and blacksmiths. Among Luba living in the region today, anvils are both forging tools and royal regalia. Iron pins resembling those found in the Kamilamba grave are called vinyundo (“little anvils”); they adorn a variety of ritual objects and assure community prosperity through the transformative powers of iron.  Photograph of the excavated burial known as Tomb 7 at Kamilamba. The circled areas highlight the axe blade and pins (above the figure’s bent knees) and the anvil (beside his skull). Photograph of the excavated burial known as Tomb 7 at Kamilamba. The circled areas highlight the axe blade and pins (above the figure’s bent knees) and the anvil (beside his skull).

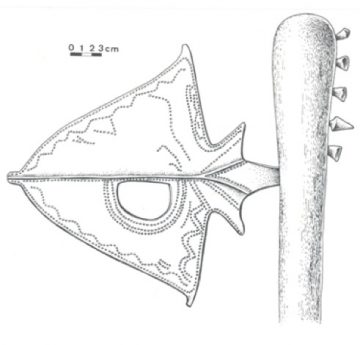

Rendering of axe blade with wood handle ornamented by pins (based on artifacts at Tomb 7, Kamilamba)

Drawing by Yvette Pacquay, 1992© Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren Rendering of axe blade with wood handle ornamented by pins (based on artifacts at Tomb 7, Kamilamba)

Drawing by Yvette Pacquay, 1992© Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

Detail of iron axe blade and pins at Tomb 7, KamilambaPhotographs by Pierre de Maret, Kamilamba, Upemba Region, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1992© Pierre de Maret and Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

Great Zimbabwe Detail of iron axe blade and pins at Tomb 7, KamilambaPhotographs by Pierre de Maret, Kamilamba, Upemba Region, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1992© Pierre de Maret and Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

Great Zimbabwe

Iron tribute. Today, Great Zimbabwe is the site of the most extensive ruins in Africa south of the Sahara. In the 13th and 14th centuries CE, when it was the principal city of a major state, its population exceeded 10,000 inhabitants. The substantial number of iron hoe blades found together outside the Great Enclosure confirms that locally forged tools enabled agriculture on a scale to feed many thousands. These blade forms were probably also used as currencies. Because no large slag mounds have been found at or near the site, iron production likely occurred throughout the area. This suggests a tribute system through which taxation of small production sites met the demand for iron at Great Zimbabwe.  Great Zimbabwe’s stone walls, erected without mortar, celebrated the status of the city’s elite rather than serving defensive purposes. Their residences were probably surrounded by the elliptically shaped Great Enclosure, shown here from inside. The conical tower may have symbolized tribute in grain and the king’s ability to feed his people; in shape it resembles the granaries still used by Shona peoples in southern Africa.Photograph by William J. Dewey, 1984

Iron and Cosmologies | Dogon and Mythical Nommo Great Zimbabwe’s stone walls, erected without mortar, celebrated the status of the city’s elite rather than serving defensive purposes. Their residences were probably surrounded by the elliptically shaped Great Enclosure, shown here from inside. The conical tower may have symbolized tribute in grain and the king’s ability to feed his people; in shape it resembles the granaries still used by Shona peoples in southern Africa.Photograph by William J. Dewey, 1984

Iron and Cosmologies | Dogon and Mythical Nommo

Dogon artistMaliRitual figure19th centuryIronDr. Jan Baptiste BedauxReaching skyward. This unusual form possesses upstretched arms, perhaps asking for rain, and two rings suspended by chains. Dogon smiths forge such figures for placement on shrines or to strike on the ground during ritual acts.Storied smiths. Many African communities, such as the Dogon and Bamana of Mali, use origin stories to call attention to the brilliant inventions and innovations of blacksmiths. A Dogon origin story tells of how the Supreme Being, Amma, lived in the “Above” with protohumans called nommo, one of whom had the audacity to steal a piece of the sun—fire—to bring down to the earth along with other elements necessary to nature and human life. Infuriated, Amma hurled lightning after the fleeing nommo, causing its ark to crash and dispersing plants, animals, and humans across the earth. Since Dogon cosmology considers fire the essence of divine power and the source of life, Dogon blacksmiths are revered for putting fire to use in producing ritual objects and tools essential to farming. Dogon artistMaliRitual figure19th centuryIronDr. Jan Baptiste BedauxReaching skyward. This unusual form possesses upstretched arms, perhaps asking for rain, and two rings suspended by chains. Dogon smiths forge such figures for placement on shrines or to strike on the ground during ritual acts.Storied smiths. Many African communities, such as the Dogon and Bamana of Mali, use origin stories to call attention to the brilliant inventions and innovations of blacksmiths. A Dogon origin story tells of how the Supreme Being, Amma, lived in the “Above” with protohumans called nommo, one of whom had the audacity to steal a piece of the sun—fire—to bring down to the earth along with other elements necessary to nature and human life. Infuriated, Amma hurled lightning after the fleeing nommo, causing its ark to crash and dispersing plants, animals, and humans across the earth. Since Dogon cosmology considers fire the essence of divine power and the source of life, Dogon blacksmiths are revered for putting fire to use in producing ritual objects and tools essential to farming.

Dogon peoples live in Mali on the remote edge of the Sahara, where farming is precarious due to sandy soil and scarce rains. Their complex philosophical and religious systems help them understand the perils and purposes of life. Iron and Cosmologies | Bamana Blacksmith LeadersThe stuff of legend. The prominent role of blacksmiths in Bamana society derives from their expertise in ironworking technologies, herbal medicines, and management of relations with the supernatural. Bamana smiths lead the powerful Kòmò initiation association, which teaches its members to marshal exceptional energies called nyama to address the personal, social, and spiritual concerns people face in life. Kòmò encompasses a triangle of power: blacksmith leaders, power objects including masks and altars, and wilderness spirits. Indeed, Kòmò is a daunting thing of the bush, brought into civilized spaces by ironsmiths. The importance of blacksmiths is stressed in Bamana oral traditions, including the well-known 14th-century Sunjata Epic, which describes the founding of the ancient Empire of Mali (different from today’s republic of Mali). |

【本文地址】

When and how did iron smelting and forging technologies emerge in Africa south of the Sahara? Archeologists once thought that knowledge of making iron had arrived in northern Africa by the first millennium BCE, later spreading to the south, but more recent research has pushed the advent of iron production farther back in time.

When and how did iron smelting and forging technologies emerge in Africa south of the Sahara? Archeologists once thought that knowledge of making iron had arrived in northern Africa by the first millennium BCE, later spreading to the south, but more recent research has pushed the advent of iron production farther back in time.